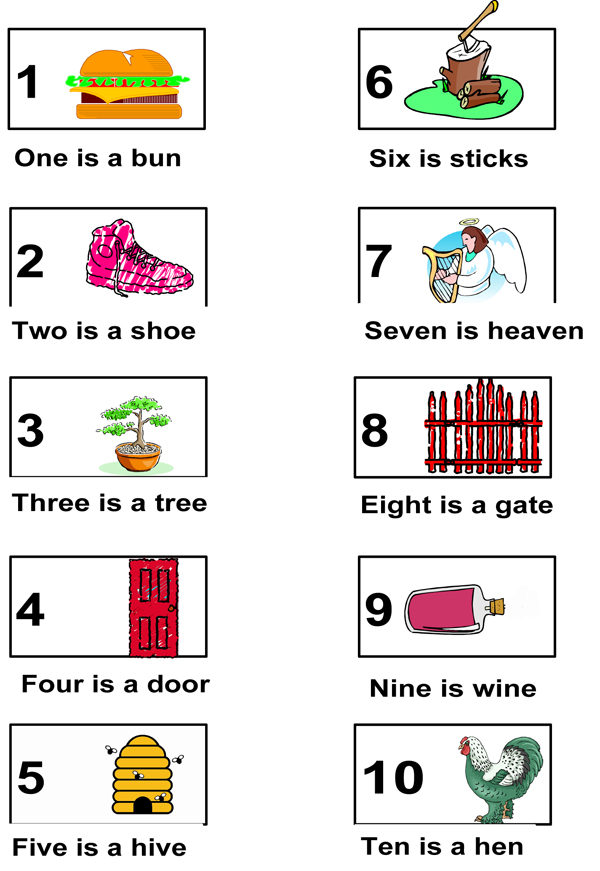

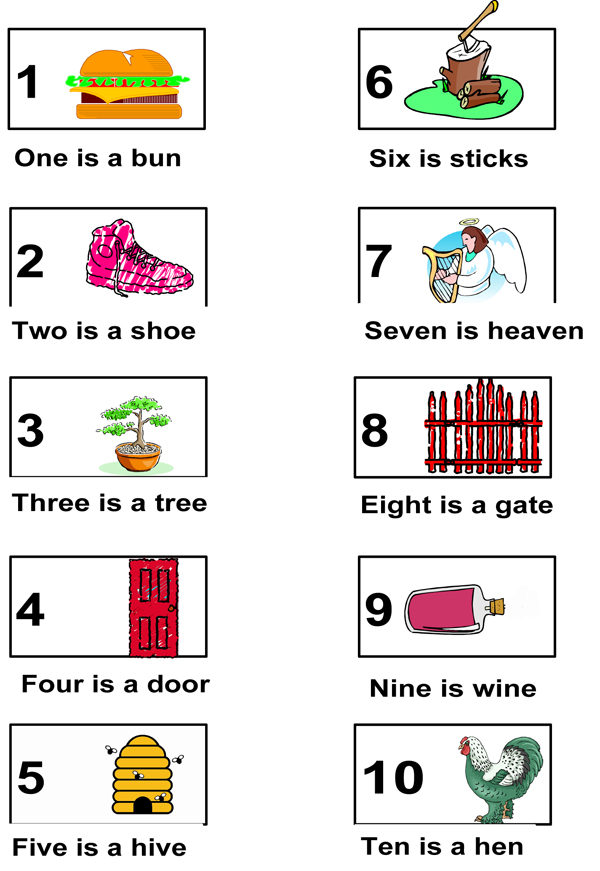

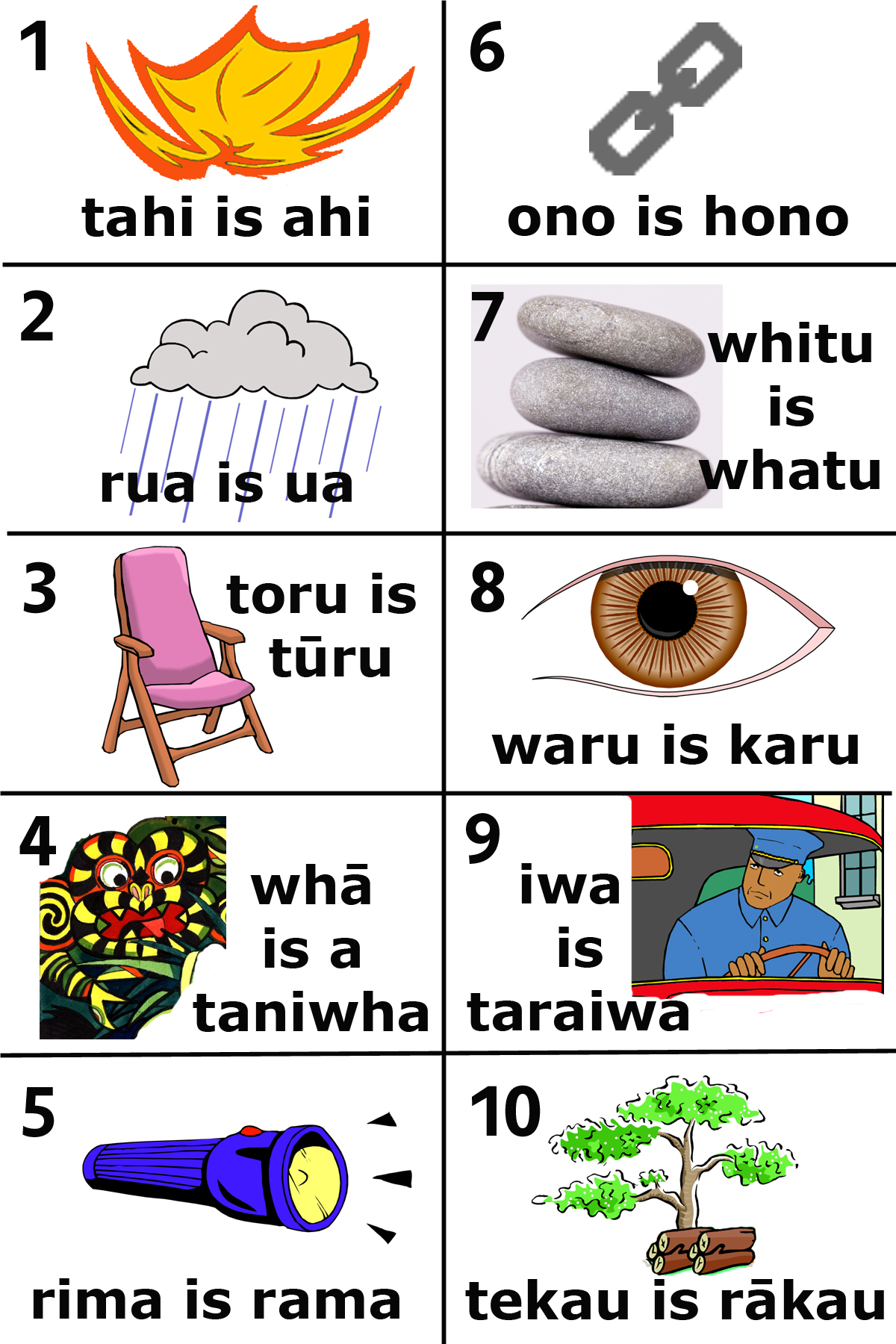

If you have a numbered list to memorize, the best mnemonic strategy is the pegword mnemonic. This mnemonic uses numbers which have been transformed into visual images. Here's the standard 1-10 set.

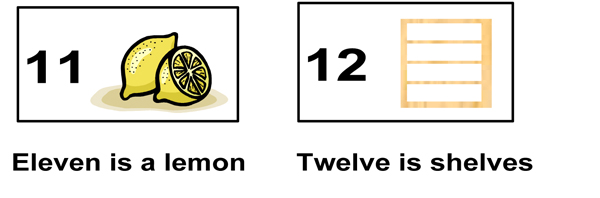

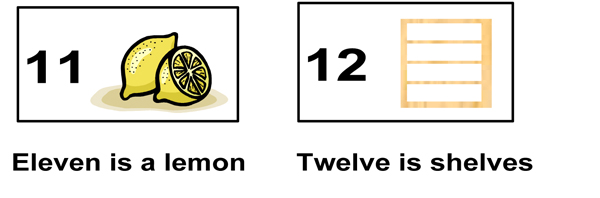

I add two more:

If you have a numbered list to memorize, the best mnemonic strategy is the pegword mnemonic. This mnemonic uses numbers which have been transformed into visual images. Here's the standard 1-10 set.

I add two more:

Learning a new language is made considerably more difficult if that language is written in an unfamiliar script. For some, indeed, that proves too massive a hurdle, and they give up the attempt.

Brain tissue is divided into two types: gray matter and white matter. These names derive very simply from their appearance to the naked eye. Gray matter is made up of the cell bodies of nerve cells. White matter is made up of the long filaments that extend from the cell bodies - the "telephone wires" of the neuronal network, transmitting the electrical signals that carry the messages between neurons.

The volume of gray matter tissue - a measure you will see cited in various reports - is a measure of the density of brain cells in a particular region.

Alzheimer's disease currently affects one in 10 people over age 65 and nearly half of those over age 85.

More than 19 million Americans say they have a family member with the disease, and 37 million say they know somebody affected with Alzheimer's.

In the United States, the average lifetime cost per Alzheimer patient is US$174,000. (These figures are from the U.S. Alzheimer's Association).

We must believe that groups produce better results than individuals — why else do we have so many “teams” in the workplace, and so many meetings. But many of us also, of course, hold the opposite belief: that most meetings are a waste of time; that teams might be better for some tasks (and for other people!), but not for all tasks. So what do we know about the circumstances that make groups better value?

Find out about the pegword mnemonic

To celebrate Māori Language Week here in Aotearoa (New Zealand), I've put together a pegword set in te reo:

At the same time as a group of French parents and teachers have called for a two-week boycott of homework (despite the fact that homework is officially banned in French primary schools), and just after the British government scrapped homework guidelines, a large long-running British study came out in support of homework.

A lot of theories have been thrown up over the years as to what we need sleep for (to keep us wandering out of our caves and being eaten by sabertooth tigers, is one of the more entertaining possibilities), but noone has yet been able to point to a specific function of the sleep state that would explain why we have it and why we need so much of it.

Brain autopsies have revealed that a significant number of people die with Alzheimer’s disease evident in their brain, although in life their cognition wasn’t obviously impaired. From this, the idea of a “cognitive reserve” has arisen — the idea that brains with a higher level of neuroplasticity can continue to work apparently normally in the presence of (sometimes quite extensive) brain damage.

When considering what will be the most effective strategies for you, don't forget the basic principles of memory:

(1) Repetition repetition repetition

The trick is to find a way of repeating that is interesting to you. This is partly governed by level of difficulty (too easy is boring; too difficult is discouraging). The point is to find an activity (more than one, in fact), which enable you to hold on to your motivation through sufficient repetitions to drive them into your head. Bear in mind, too, the importance of:

(2) Changing context