Have we really forgotten how to remember?

A new book, Moonwalking with Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything, has been creating some buzz recently. The book (I haven’t read it) is apparently about a journalist’s year of memory training that culminated in him making the finals of the U.S.A. Memory Championships. Clearly this sort of achievement resonates with a lot of people — presumably because of the widespread perception that forgetfulness is a modern-day plague, for which we must find a cure.

Let’s look at some of the points raised in the book and the discussion of it. There’s the issue of disuse. It’s often argued that technology, in the form of mobile phones and computers, means we no longer need to remember phone numbers or addresses. That calculators mean we don’t need to remember multiplication tables. That books mean we don’t need to remember long poems or stories (this one harks back to ancient times — the oft-quoted warning that writing would mean the death of memory).

Some say that we have forgotten how to remember.

The book recounts the well-known mnemonic strategies habitually used by those who participate in memory championships. These strategies, too, date back to ancient times. And you know something? Back then, just like now, only a few people ever bothered with these strategies. Why? Because for the most part, they’re far more trouble than they’re worth.

Now, this is not to say that mnemonic strategies are of no value. They are undoubtedly effective. But to achieve the sort of results that memory champions aspire to requires many many hours of effort. Moreover, and more importantly, these hours do not improve any other memory skills. That is, if you spend months practicing to remember playing cards, that’s not going to make you better at remembering the name of the person you met yesterday, or remembering that you promised to pick up the bread, or remembering what you heard in conversation last week. It’s not, in fact, going to help you with any everyday memory problem.

It may have helped you learn how to concentrate — but there are far more enjoyable ways to do that! (For example, both Lumosity and Posit Science offer games that are designed to help you improve your ability to concentrate. Both programs are based on cognitive science, and are run by cognitive scientists. Both advertise on my website.)

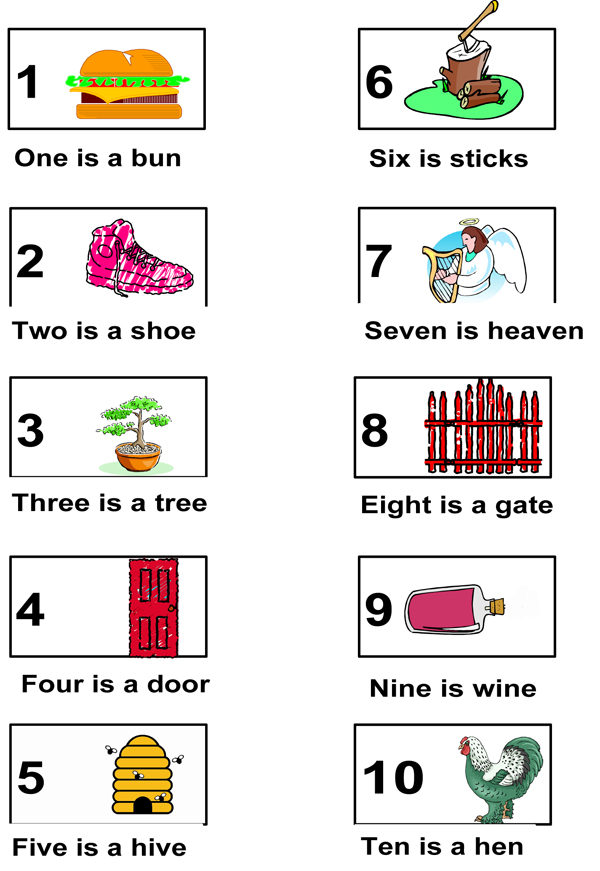

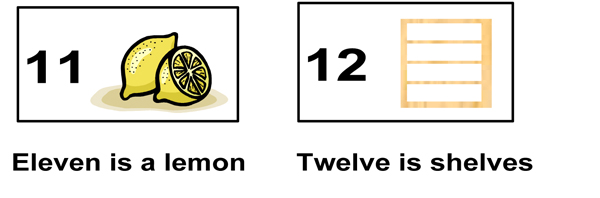

Does it matter that we can’t remember phone numbers? It’s argued that being unable to remember the phone numbers of even your nearest and dearest, if your phone has a melt-down, is a problem — although I don’t think anyone’s arguing that it’s a big problem. But if you are fretting about not being able to remember the numbers of those most important to you, the answer is simple, and doesn’t require a huge amount of training. Just make sure you make the effort to recall the number each time before you use it. After a while it’ll come automatically, and effortlessly, to mind (assuming that these are numbers you use often). If there’s a number you don’t use often, but don’t want to write down or record digitally, then, yes, a mnemonic is a good way to go. But again, you don’t have to get wildly complicated about it. The sort of complex mnemonics that memory champs use are the sort required for very fast encoding of many numbers, words, or phrases. For the occasional number, a few simple tricks suffice.

Shopping lists are another oft-quoted example. Sure, we’ve all forgotten to buy something from the supermarket, but it’s a long way from that problem and the ‘solution’ of complicated mnemonic images and stories. Personally, I find that if I write down what I want from the shop, then that’s all I need to do. Having the list with you is a reassurance, but it’s the act of writing it down that’s the main benefit. But if someone else in the household adds items, then that requires special effort. Similarly, if the items aren’t ‘regular’ ones, then that requires a bit more effort.

I have an atavistic attachment to multiplication tables, but is it really important for anyone to memorize them anymore? A more important skill is that of estimation — where so many people seem to fall down is in not realizing, when they perform a calculation inaccurately, that the answer is unlikely and they’ve probably made an error. More time getting a ‘feel’ for number size would be time better spent.

Does it matter if we can’t remember long poems? Well, I do favor such memorization, but not because failing to remember such things demonstrates “we don’t know how to remember anymore” . I think that memorizing poems or speeches that move us ‘furnishes the mind’, and plays a role in identity and belongingness. But you don’t need , and arguably shouldn’t use, complex mnemonic strategies to memorize them. If you want to ‘have’ them — and it has been argued that it is only by memorizing a text that you can make it truly yours — then you are better spending time with it in a meaningful way. You read it, you re-read it, you think about it, you recite the words aloud because you enjoy the sound of the words, you repeat them to friends because you want to share them, you dwell on them. You have an emotional attachment, and you repeat the words often. And so, they become yours, and you have them ‘in your heart’.

Memorizing a poem you hate because the teacher insists is a different matter entirely! And though you can make the case that children have to be forced to memorize such verse until they realize it’s something they like, I don’t think that’s true. Children ‘naturally’ memorize verse and stories that they like; it’s forced memorization that has engendered any dislike they feel.

Anyway, that’s an argument for another day. Let’s return to the main issue: have we forgotten how to remember?

No.

We remember naturally. We forget naturally too. Both of these are processes that happen to us regardless of our education, of our intelligence, of our tendencies to out-source part of our memory. We have the same instinctive understanding of how to remember that we have always had, and the ability to remember long speeches or sagas is, as it has always been, restricted to those few who want the ability (bards, druids, Roman politicians).

It’s undeniably true that we forget more than our forebears did — but we remember more too. The world’s a different place, and one that puts far greater demands on memory than it ever did. But the answer’s not to pine after a ‘photographic memory’, or the ability to recite the order of a deck of playing cards after seeing them once. For almost all of us, that ability is too hard to come by, and won’t help us with any of the problems we have anyway.

The author of this memoir is reported as saying that the experience taught him “to pay attention to the world around” him, to appreciate the benefits of having a mental repository of facts and texts, to appreciate the role of memory in shaping our experience and identity. These are all worthwhile goals, but you can rest assured that there are better, more enjoyable, ways of achieving them. There are also better ways of improving everyday memory. And perhaps most importantly, better ways of achieving knowledge and expertise in a subject. Mnemonics are an effective strategy for memorizing meaningless and arbitrary information, and they have their place in learning, but they are not the best method for learning meaningful information.

Let me add that by no means am I attacking Joshua Foer’s book, memory championships, or those who participate in them. I’m sure the book is an entertaining and enlightening read; memory championships are fully as worthwhile as any sport championship; those who participate in them have a great hobby. I have merely used this event as a springboard for offering some of my thoughts on the subject.

Here are the links that provoked this post. Two reviews of Joshua Foer’s book:

http://www.theguardian.com/science/2011/mar/13/memory-techniques-joshua…

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/08/books/08book.html

An account and a video of a high school team’s winning of the US memory championship (high school division)

http://video.nytimes.com/video/2011/03/09/sports/100000000710149/memory…

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/10/sports/10memory.html

Addendum:

After writing this, I discovered another article, this time by Foer himself. He makes a couple of points I’ve made before, but are well worth repeating. Until a few hundred years ago, there were very few copies of any text, and therefore it behooved any scholar, in reading a book, to remember it as well as he could. (In passing, I’d like to note that Foer wins major points with me by quoting Mary Carruthers). Therefore, the whole way readers approached books was very different to how it is for us today, when we value range more than depth. Understandably, when there are so many texts, on so many topics. To constrict ourselves to a few books that we read over and over again is not something we should wish on ourselves. But the price of this is clear; we can all relate to Foer’s comment: “There are books up there [on my bookshelves] that I can’t even remember whether I’ve read or not.”

I was also impressed to learn that he’d taken advice from that expert on expertise, K. Anders Ericsson. And the article has a very good discussion on how to practice, and Ericsson’s work on what he calls deliberate practice (although Foer doesn’t use that name).

Finally, just to reiterate the main point of my post, Foer himself says at the end of this excellent article: “True, what I hoped for before I started hadn’t come to pass: these techniques didn’t improve my underlying memory … Even once I was able to squirrel away more than 30 digits a minute in memory palaces, I seldom memorized the phone numbers of people I actually wanted to call. It was easier to punch them into my cellphone.”

Note that you can also test your memorization abilities with games from the World Memory Championship at http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2011/02/20/magazine/memory-games.htm

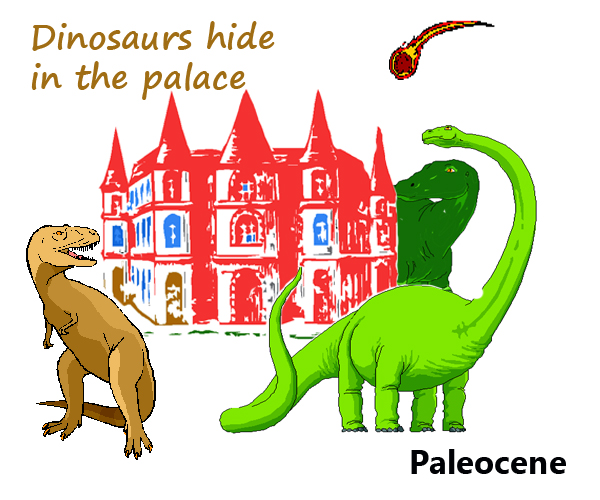

Instead of “Holograms are very recent”, you might want to form an image of someone falling into a hole (tying the Holocene to the “Age of Humans”).

Instead of “Holograms are very recent”, you might want to form an image of someone falling into a hole (tying the Holocene to the “Age of Humans”).

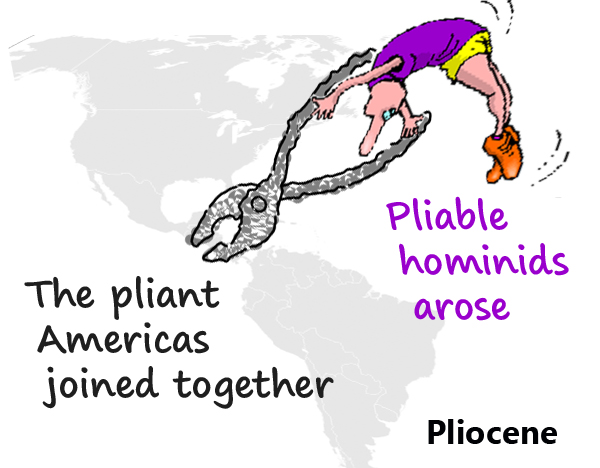

If you can visualize very limber (perhaps in distorted postures) ape-like humans, Pliable hominids might be satisfactory, or you may need to fall back on the pliers — perhaps an image of pliers bringing North and South America together.

If you can visualize very limber (perhaps in distorted postures) ape-like humans, Pliable hominids might be satisfactory, or you may need to fall back on the pliers — perhaps an image of pliers bringing North and South America together. Mild weather isn’t terribly imageable; you might like to imagine milk pouring from the joint where Africa and Eurasia have collided.

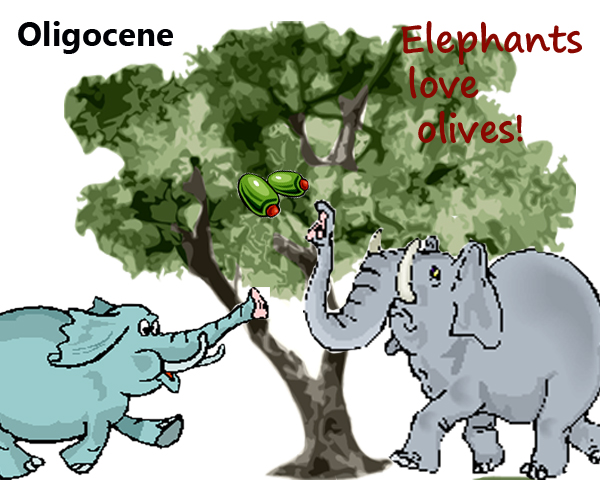

Mild weather isn’t terribly imageable; you might like to imagine milk pouring from the joint where Africa and Eurasia have collided. Oligarchs is likewise difficult, but you could visualize elephants under olive trees, eating the olives.

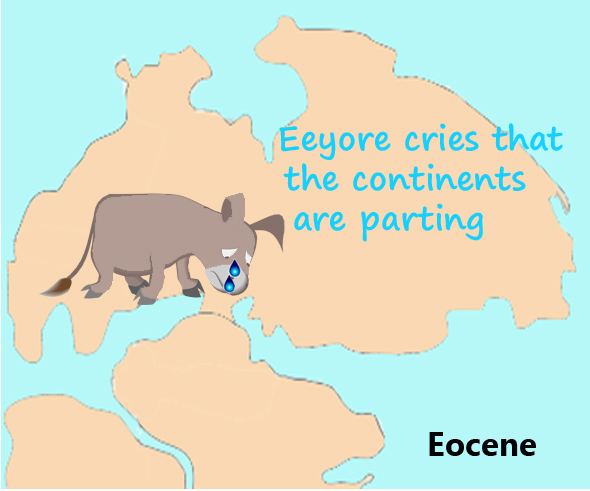

Oligarchs is likewise difficult, but you could visualize elephants under olive trees, eating the olives. And now of course, we come to the most difficult — the Eocene. Here’s a thought, for those brought up with Winnie the Pooh. If you have a clear picture of Eeyore, you could use him in this image. Perhaps Eeyore is standing on one part of the separating Laurasia (looking appropriately disconsolate).

And now of course, we come to the most difficult — the Eocene. Here’s a thought, for those brought up with Winnie the Pooh. If you have a clear picture of Eeyore, you could use him in this image. Perhaps Eeyore is standing on one part of the separating Laurasia (looking appropriately disconsolate).